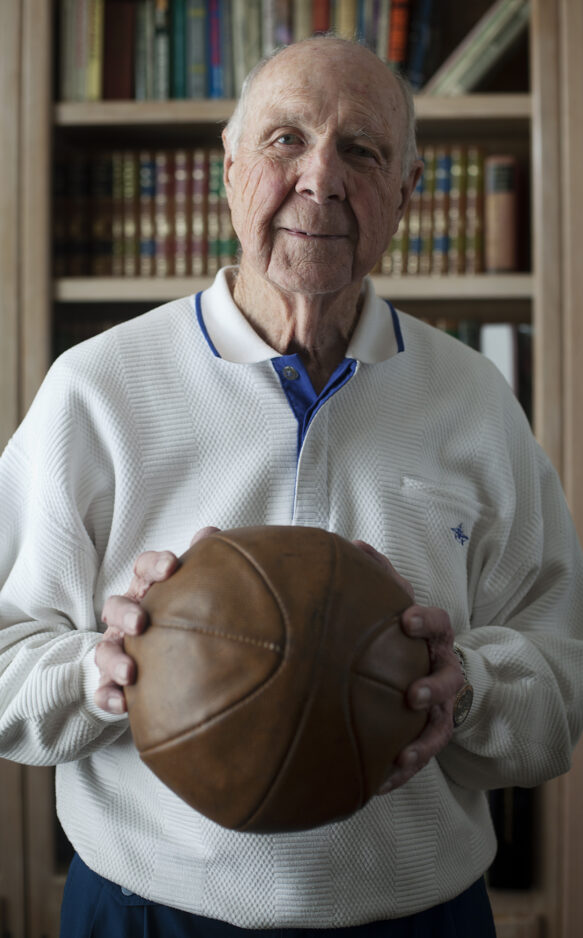

Cedar Hills man a living legend

With three seconds left in overtime of the national championship game, Herb Wilkinson had the ball passed to him. A step beyond the top of the key, he took the shot — the winning shot. The University of Utah underdog team pulled off a national championship win.

Hailed as a Cinderella story, the win compelled Phillip O. Badger, then NCAA president, to marvel.

“Thus is completed the most amazing saga in the history of collegiate basketball,” Badger said.

The year was 1944 and the war had ravaged the world. U of U coach Vadal Peterson had worked hard to put together a team. Players were deferred from the draft because they had been admitted to medical school, dental school or were under 18 years of age. Enter Wilkinson.

He’d never dreamed of becoming an All-American player. Wilkinson began high school at 5 feet 2 inches and looked up to his older, basketball-playing brother, Clayton Wilkinson, at 6 feet 3 inches.

“We walked down the halls of East High like Mutt and Jeff,” Herb Wilkinson said.

After finally hitting his growth spurt, he was able to get a suit his senior year and considered himself lucky.

“I didn’t try out for a university team and was happy to play church ball,” Wilkinson said. “I had no illusions of being an all-star university player.”

Peterson thought otherwise. He recruited the 6-foot 4-inch East High graduate along with any others he could find. Happy with a starting team of 20, they lost 11 to the draft and had only nine eligible players left. It was not even enough to scrimmage, so the assistant coach had to step in to make an even 10. The team played an unlikely nearly undefeated season and was invited to Madison Square Garden to attend the National Invitation Tournament, which at the time was larger than the NCAA.

After an unfortunate loss, they packed their bags. Meanwhile, a tragic car accident took the life of an NCAA Tournament-bound Arkansas assistant coach and the leg of a lead player .

As quickly as they left one tournemtnt, The University of Utah team was asked to fill in for Arkansas. The team accepted and was on its way to Kansas City the next day where they competed for and won the NCAA tournament.

The win had them headed back to Madison Square Garden to take on the hailed NIT winner — Dartmouth.

By this time the previously little-known Utes were becoming wildly popular. The media nicknamed the players “The Blitz Kids.” Aptly named, the little team of nine were young, many freshmen, but they also worked tirelessly creating a blitz on the court. In fact, many played the entire game back at Madison Square Garden. The game ended with Wilkinson’s unbelievable last-second shot, making the Utes the 1944 national champions.

Footage from the game not only was played for soldiers serving all over the world in 1944, but also is shown at halftime every year during March Madness at the U of U. Four of the nine original players from that team are still living and are periodically honored and introduced to the crowd — even as recently as last month.

Wilkinson went on to be an All-Star player at the University of Iowa with his brother. They played together while Herb Wilkinson finished his dental degree. Then he was drafted by the NBA’s St. Louis Bombers in 1948. He turned them down to complete a residency in oral surgery anesthesia. At the end of the year, Wilkinson received a call to serve a mission for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. At the same time, U of U teammate Arnie Ferrin, then playing for the Minneapolis Lakers, called needing a good guard. He asked Wilkinson if he would be interested in trying for a spot on the team. The church deferred the call for Wilkinson to play ball for a season with the Lakers.

Wilkinson’s story didn’t end with being a basketball hero, though. His wife said he’s a hero to their family. He married Dorothy Curtis after all of his ball playing was over.

“Herb never even talked about basketball when we were dating,” Dorothy Wilkinson said. “He didn’t even take me to a sporting event. It wasn’t until just before we married that Clayton’s wife brought out all of these newspaper articles about Herb. I had no idea that he had been a big basketball star.”

She also didn’t know this big basketball star had made big sacrifices. When asked to join the Minneapolis Lakers, he said that he would sign a contract only if it included that he would not play on Sundays. With the coach’s support he played a lot during those preseason games but not on Sundays. During the final preseason game, the owner came and found him missing. Wilkinson was at church. The owner said Wilkinson had to play on Sundays or be released from the team. Wilkinson gave up an NBA career with the potential fame and money that accompanied and left to serve a full-time mission in Great Britain.

“It was very difficult,” Herb Wilkinson said. “I would have played for free just to be able to play, but playing on Sunday was just not something that I was willing to negotiate.”

During his mission in Great Britain, Finland wanted to begin an Olympic basketball team and called and asked the church if they could borrow Wilkinson to coach the team. The church agreed. For the next month, Wilkinson coached by day and taught religious cottage meetings by night.

Throughout his life, he has continued to receive honors. In 2002 he was named one of the top 20 players in 100 years at the University of Iowa. At age 77, Wilkinson began participating in the track and field events at various senior games. This summer, at age 89, he won a silver medal and four golds at the Huntsman Senior Games in St. George. This is the largest senior tournament and is patterned after the Olympics with more than 90 countries represented by more than 10,000 athletes. In the last 12 years, Wilkinson has won more than 160 medals.

He attributes his good health to clean living and exercising at least three times a week with a combination of racquetball, weights and stretching. He says his balance and eyesight are sharper since playing racquetball.

“You’ve heard people say, use it or lose it. It’s true,” Wilkinson said. “I move a lot better because of exercise. You see old people shuffle along. I try not to look like an old person.”

Together the Wilkinsons raised five children and carefully taught a daughter with cerebral palsy to make milestones throughout her life defying all doctors’ predictions.

“I would rather be known for being a good solid citizen and church member than for being a basketball player,” Wilkinson said. “Basketball has given me a lot of real fun and enjoyment, but it is not the most important thing. The Huntsman games are not the most important things. They are just a part of life. That life has been a marvelous trip. I’ve enjoyed most every minute, and the family of course is the most important — more important than anything else.”