Searching for solutions: Utah Valley University scientists lead charge to combat water contamination in Peru

- Utah Valley University biologist Lauren Brooks and Eddy Cadet, rear, conduct testing at a water treatment plant in Lima, Peru, on March 25, 2025.

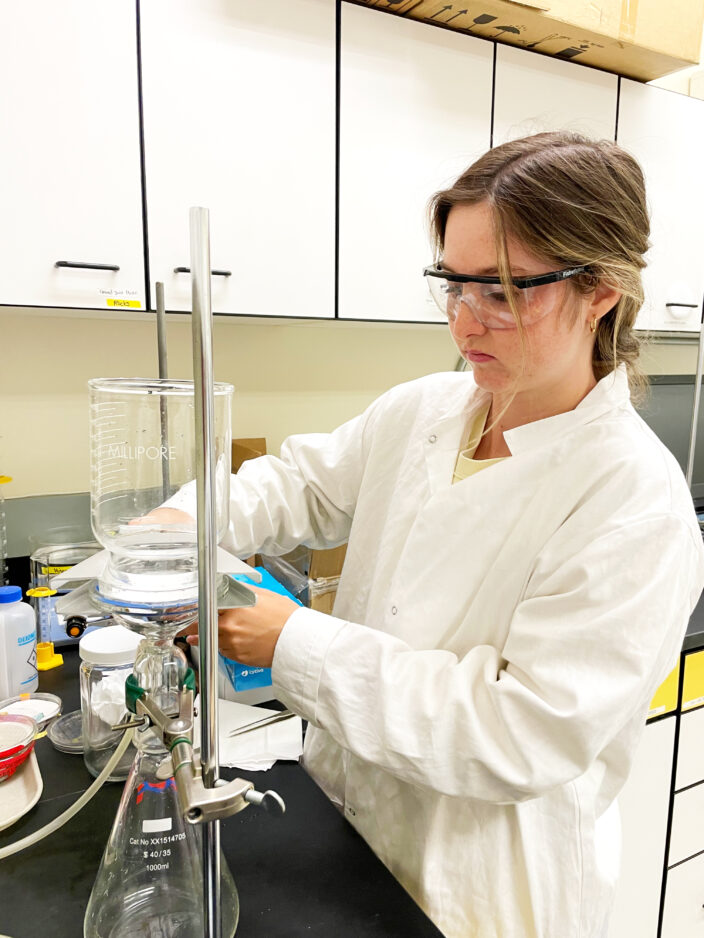

- Utah Valley University student Elliet Leaver tests water on Tuesday, Aug. 19, 2025.

- Eddy Cadet, right, and others tests water for contamination during a project in Lima, Peru, on March 27, 2025.

- Utah Valley University biologist Lauren Brooks collects a water sample during a project to test for contamination in Lima, Peru, on March 27, 2025.

Scientists at Utah Valley University are stepping up to tackle an international water crisis.

Faculty members and students from UVU’s College of Science have been exploring severe contamination issues throughout Peru.

The collaborative effort between UVU and Peruvian leaders and universities examines local water sources used for drinking, cooking and bathing.

Their findings revealed toxic elements such as fecal matter, trace metals, microplastics, arsenic and bacteria are present in the South American country’s water.

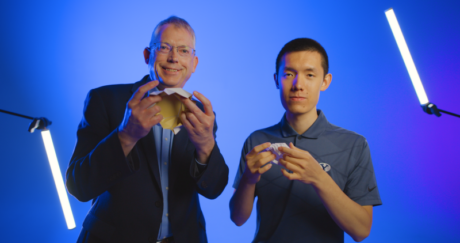

The idea for the global project was sparked after UVU presented their findings on Utah Lake’s water quality, level of pollution and sustainability before Peruvian congressional leaders during a 2024 visit to Utah.

According to UVU, Baldomero Lago, who is the head of the university’s UNESCO Chair, proposed an idea to see if similar issues are present in Peru.

“During that meeting, he floated an idea: What if similar environmental issues existed in Peru’s lakes and water systems? What if UVU partnered with Peruvian institutions to find out?” a UVU press release said.

Roughly 50% of the population in Peru lack access to safe drinking water, according to water.org.

Shortly after the 2024 gathering, a partnership was born and their work began.

UVU biologist Lauren Brooks is one of several faculty members leading the water-testing initiative in Peru.

Brooks and others traveled to the South American country in March; she recalled the severity of the issue after realizing the water she collected for testing was still contaminated after sterilization.

“Even after rigorous sanitation, the water was still unsafe,” she said. “And this is water people are using to cook, clean and drink every day.”

According to Peruvian leaders, at least one culprit behind the contamination is mining operations that dominate the country’s economy.

Brooks recounted a visit to a local woman’s house, where they tested her tap water and discovered fecal contamination, further highlighting the need for safe water access in Peru.

The implications of unsanitary water means local citizens often resort to boiling water or buying it in bottles.

“We were lucky that we were able to purchase bottled water, but not everyone (there) can,” Brooks said. “And so you’re just dealing with that because there’s just not a lot of options if you don’t have clean, treated drinking water.”

Over a six-day period in March, the team collected 120 water samples across five municipalities. Each sample takes approximately 10 hours to fully analyze, a process now being assisted by UVU students.

Their work is far from over. Faculty members from UVU are tentatively planning another trip to Peru before the end of the year.

UVU faculty and their Peruvian counterparts plan to present their findings to the Peruvian Congress in December. They’ll also plan to meet with mayors, university leaders and community groups to discuss next steps toward possible solutions.

“Our role is to present the evidence,” Lago said. “We don’t force implementation. We’re an academic institution. That is why people trust us.”

The effort is part of UVU’s recently awarded UNESCO Chair and seeks to understand the extent of water contamination in some of the most vulnerable communities in South America, the university noted in its release.

The initiative aims to improve public health through scientific collaboration and data-driven advocacy.

Brooks said she is proud to be part of the project and of the potential of having UVU’s scientific efforts lead to policy changes.

“It has really re-inspired me,” she told the Daily Herald. “I’m so passionate about it. I want to go back, maybe do a sabbatical in Peru. It’s changing my life.”

UVU says its work in Peru is not just a scientific study; it’s a lifeline for people in vulnerable communities.