A primer on what the high seas treaty is and how it will work

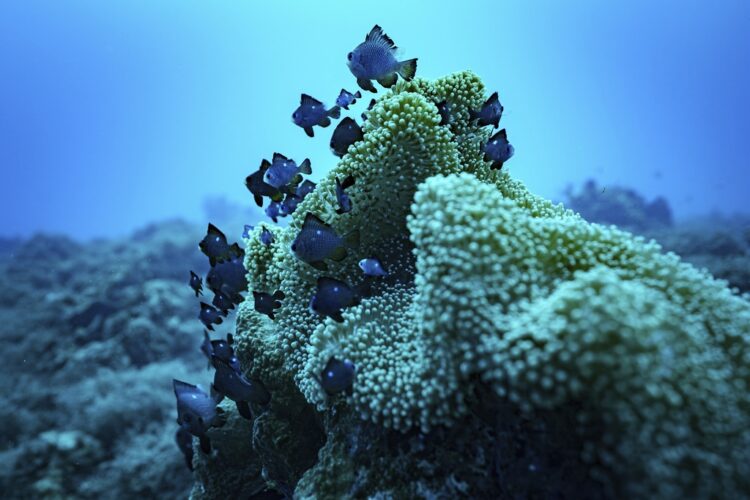

FILE - Fish swim at Havannah Harbour, off the coast of Efate Island, Vanuatu, July 20, 2025. (AP Photo/Annika Hammerschlag, File)

The approval of a high seas treaty means new protections will be possible in international waters for the first time.

Here’s a rundown of what the treaty is, why it matters and what is still to come.

It’s the first agreement to protect marine diversity

Formally known as the Agreement on Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction, the treaty is the first legally binding agreement aimed at protecting marine biodiversity in international waters. These areas, which lie beyond the jurisdiction of any single country, account for nearly two-thirds of the ocean and nearly half of Earth’s surface.

Until now, no comprehensive legal framework existed to create marine protected areas or enforce conservation on the high seas.

Climate change and other threats to the seas

Despite their remoteness, the high seas are under growing pressure from overfishing, climate change and the threat of deep-sea mining. Environmental advocates warn that without proper protections, marine ecosystems in international waters face irreversible harm.

“Until now, it has been the wild west on the high seas,” said Megan Randles, global political lead for oceans at Greenpeace. “Now we have a chance to properly put protections in place.”

The treaty is also essential to achieving what’s known as the global “30×30” target — an international pledge to protect 30% of the planet’s land and sea by 2030.

How the treaty works

The treaty creates a legal process for countries to establish marine protected areas in the high seas, including rules for potentially destructive activities like deep-sea mining and geoengineering. It also establishes a framework for technology-sharing, funding mechanisms and scientific collaboration among countries.

Crucially, decisions under the treaty will be made multilaterally through what’s called a conference of the parties rather than by individual countries acting alone.

What comes next

Ratification Friday by a 60th nation triggered a 120-day countdown before the treaty enters into force. Countries can already begin planning high seas protected areas, but formal proposals will only move forward once oversight mechanisms and decision-making rules are established.

The first conference of the parties must be held within a year of the treaty taking effect. It will lay the groundwork for implementation, including decisions on governance, financing and the creation of key bodies to evaluate marine protection proposals.

Environmental groups are pushing for even more countries to ratify the treaty and to do so quickly — the more countries that ratify, the stronger and more representative the treaty’s implementation will be. There’s a carrot for countries to do so. Only those that ratify by that first conference will be eligible to vote on critical decisions that determine how the treaty will operate.